Intersecting Families, Trees, and Spreadness

Addendum (09 April 2025): Several people have told us about a minor mistake in our application of the LLLL. We have an internal version which corrects this. At some point we will correct our preprint on the arXiv. With 7 authors decision making takes some time.

Intersecting families and, in particular, the Erdős-Ko-Rado theorem were a central part of my PhD thesis many years ago. Thus, I am always happy to come back to these type of problems. This post is to discuss my recent preprint on intersecting trees! It is in joint work with Péter Frankl, Glenn Hurlbert, Andrey Kupavskii, Nathan Lindzey, Karen Meagher, and Venkata Raghu Tej Pantangi.

Here is the problem: Consider the set ${\mathcal{T}}$ of spanning trees of ${K_n}$, the complete graph on ${n}$ vertices. What is the size of the largest family of pairwise intersecting trees? What is its structure? We say that two trees are intersecting if they share at least one edge.

This goes back a long time. In 2016, when I was a postdoc in Jerusalem with Gil Kalai, Gil asked me about intersecting families of trees. But I had no good ideas. Luckily, if you wait long enough, then others develop new techniques which help you solve your problem. This partially happened with the introduction of the concept of spreadness. But that was not enough. We actually needed three attempts to solve the problem. For each of the three we thought for some time that we are done, just to find a mistake. This I want to describe here. I refer to the preprint for a nice motivation for this problem related to the Nash-Williams’ theorem.

Attempt 1: Shifting

As a reminder: The Erdős-Ko-Rado theorem, in its easiest version, states that an intersecting family ${\mathcal{F}}$ of ${k}$-uniform sets of ${n := \{1, \ldots, n \}}$ has size at most ${\binom{n-1}{k-1}}$ (for ${n \geq 2k}$). Here equality occurs for ${n \geq 2k+1}$ if and only if ${\mathcal{F}}$ consists of all ${k}$-uniform sets.

But what happens if instead of having all ${k}$-uniform sets, we have a subset ${\mathcal{G}}$ of the ${k}$-uniform sets? In a very beautiful result, published recently in Advances of Mathematics, Andrey Kupavskii and Dimitrii Zakharov did show that this is fine if ${\mathcal{G}}$ is ${r}$-spread and ${(r, t)}$-spread. Loosely, speaking, this means that ${\mathcal{G}}$ is very far from being an intersecting family (it is “spread out”?).

Definition Given ${r > 1}$, a family ${\mathcal{G} \subseteq 2^{[m]}}$ is ${r}$-spread if

$$|\mathcal{G}(X)| \leq r^{-|X|} \cdot |\mathcal{G}| $$ for all ${X \subseteq [m]}$. Here ${\mathcal{G}(X) = \{ G \in \mathcal{G}: X \subseteq G \}}$.

The definition of ${(r, t)}$-spreads is similar, just that there also a ${t}$-set ${T}$ occurs such that

$$ |\mathcal{G}(U)| \leq r^{-(|U|-|T|)} \cdot |\mathcal{G}(T)| $$ for all ${T \subseteq U \subseteq [m]}$. Informally, Kupavskii and Zakharov did show the following:

Theorem (Very Informal) Suppose that ${\mathcal{G}}$ is ${(r, t)}$-spread. Let ${\varepsilon \in (0, 1)}$. If ${\mathcal{F} \subseteq \mathcal{G}}$ is a large intersecting family, then, for ${m}$ sufficiently large, ${(1-\varepsilon)|\mathcal{F}|}$ elements of ${\mathcal{F}}$ contain some fixed element.

This makes everything much easier as soon as our structure ${\mathcal{G}}$ is ${(r, t)}$-spread. We can identify spanning trees of ${K_n}$ with their edge set. Then ${m = \binom{n}{2}}$ and the family of spanning trees is ${(n/2, n-1)}$-spread. This Karen Meagher and I noticed in 2022 when I visited her in Regina. All that was left to do was to take care of the ${\varepsilon |\mathcal{F}|}$ leftover. We tried the following:

2. EKR and Spreadness

What we did try in 2022 was shifting. See this nice survey by Péter Frankl for some examples. What is the basic idea? Consider the following operations on a family ${\mathcal{F}}$ and ${F \in \mathcal{F}}$:

$$ S_{ij}(F) = \begin{cases} (F \setminus \{j\}) \cup \{ i\} \text{ if } i \notin F, j \in F, (F \setminus \{j\}) \cup \{ i\} \notin F,\\ F \text{ otherwise.} \end{cases} $$ and

$$ S_{ij}(\mathcal{F}) = \{ S_{ij}(F): F \in \mathcal{F} \}. $$ If ${\mathcal{F}}$ is intersecting, then ${S_{ij}(\mathcal{F})}$ is also intersecting. This technique allows for incredibly short and elegant proofs as shifted intersecting families have far more structure than intersecting families in general. Alas, all our countless attempts at a successful shifting operation for trees failed (or, at the very least, we could not show that they work). This is not too unusual. Shifting is very delicate thing as soon as one moves away from set systems. There are quite many papers which claim to prove EKR-type results with shifting for structures other than sets which are flawed in one way or another.

We never found a shifting which survived scrutiny and some time in 2022 I gave up.

3. Attempt 2: Interlacing

Luckily, Karen did not give up, but asked others about the problem at a meeting of the Canadian Mathematical Society (CMS) which was attended by Andrey, Glenn, Nathan and Raghu. Not me, so I cannot say precisely what happened there, except that they found a nice argument for handling the remainder. The key ingredient is interlacing together with Kirchhoff’s matrix-tree theorem:

Kirchoff’s Matrix-Tree Theorem Given a connected graph ${G}$ with ${\lambda_1, \ldots, \lambda_{n-1}}$ being the non-zero eigenvalues of its Laplacian matrix, the number of spanning trees of ${G}$ is ${\frac1n \lambda_1\lambda_2 \cdots \lambda_{n-1}}$.

Picture by Júlio Reis, CC BY-SA 3.0.

If ${G = K_n}$ is the complete graph, then ${\lambda_i = n}$ for all ${i}$. Thus, we get Cayley’s formula of ${n^{n-2}}$ labelled trees. To finish our proof, we need to estimate the number of trees which avoid a fixed edge, but still meet many of our trees through that fixed edge. This can be phrased as a question about the number of spanning trees in a graph which has a spectrum very close to that of ${K_n}$. After some non-trivial (but not too terrible) estimates, this solves the problem.

There was only one issue: We did not want to solve the problem for intersecting trees. We wanted to solve it for ${t}$-interesting trees, that is, any two pairs of trees have ${t}$ edges in common. Our argument for ${t}$-intersecting trees looked all good for several months. But then one of us noticed an indexing error in our argument for estimating the ${\lambda_i}$. This did not matter for ${t=1}$, so intersecting trees, but already for ${t=2}$ we could not rescue this. Thus, we had to move on to yet another idea.

4. Attempt 3: The Lopsided Lovász Local Lemma

Luckily, one of us was always unhappy about the interlacing argument as it felt stylistically and morally wrong to them. (Not me. I have neither style nor morals.) They already suggested a new proof before we noticed that our interlacing-matrix-theorem proof was wrong! Morally, what is happening? If we have an edges ${e, f}$ and we randomly draw a tree ${T}$ which contains ${e}$, what is the chance that it contains ${f}$ as well? At most ${2/n}$. This leads to the concept of a negative dependency graph.

Definition Let ${A_1,A_2,\ldots, A_N}$ be events. A negative dependency graph is a simple graph ${G = ([N],E)}$ such that

$$ \Pr \left [\bigwedge_{j \in S} \bar{A}_j \right ] \neq 0 \Rightarrow \Pr\left [A_i~\bigg |\bigwedge_{j \in S} \bar{A}_j \right ] \leq \Pr[A_i] $$ for all ${i \in [N]}$ and ${S \subseteq \{ j \in [N] : \{i,j\} \notin E\}}$.

In 2013, Lu, Mohr, Szekely showed exactly what we needed for our problem:

Lu, Mohr, Szekely (2013) Let ${\mathcal{F}}$ be a family of forests of ${K_n}$. The graph of events ${\{ A_F: F \in \mathcal{F} \}}$, where ${A_F \sim A_{F’}}$ if there exist connected components of ${C}$ of ${F}$ and ${C’}$ of ${F’}$ that are neither identical nor disjoint, is a negative dependency graph.

With this tool in hand one can apply the Lopsided Lovász Local Lemma due to Erdős and Spencer:

LLLL Let ${A_1,A_2,\ldots, A_N}$ be events with negative dependency graph ${G = ([N],E)}$. If ${x_1,x_2,\ldots,x_N \in [0,1)}$ and

$$ \Pr[A_i] \leq x_i \prod_{ij \in E} (1-x_j) \quad \text{ for all } i \in [N], $$ then

$$ \Pr\left [\bigwedge_{i=1}^N \bar{A}_i \right ] \geq \prod_{i=1}^N (1-x_i) > 0. $$

Now our spreadness property gives us than for large enough ${n}$, a large intersecting family ${\mathcal{F}}$ consists mostly of tree which contain the edge ${e}$. We want to control the remainder of all trees in ${\mathcal{F}}$ which do not contain ${e}$. Note the remainder is not empty: A star always intersects all other trees. For all non-star trees we want to show that if we have a tree ${T \in \mathcal{F}}$ with ${e \notin T}$, then ${\mathcal{F}(\{e\})}$ must be quite small. This is probably the main source of all the difficulty whatever argument we use, it needs to work for a tree with one vertex of degree ${n-2}$, but it cannot work for a tree with one vertex of degree ${n-1}$.

Our basic setup is the following dichotomy:

Case 1: If ${T}$ has no vertex with a large degree (whatever large means), then the LLLL solves this for us.

Case 2: If ${T}$ has a vertex of relatively large degree (but not a star), then we remove that vertex from ${T}$ and ${K_n}$. This needs to be done carefully (again: it fails for ${T}$ a star), but in the end we get a forest ${T’}$ of ${K_{n-1}}$ with fewer high degree vertices. We continue doing this till we are in case 1.

This, our third attempt, made it into our preprint and solves the problem in the generality which we desired.

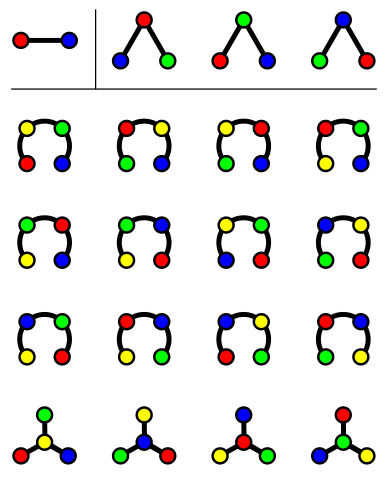

Chinese Name

Lastly, a Chinese friend told me not long ago that I should adopt a Chinese name. We discussed this important matter for several days and I consulted several more Chinese friends and acquaintances. In the end, I opted for 伊林格. As you can see, it has three pairwise non-interesting trees: 森.